The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

Of course, there is also Trump.

In truth, there is nothing like the World Service for the range of its topics and its deep seriousness about everyone, everywhere and everything. As the public parks are (for me) the best thing about London, so is the World Service (with Radios 4 and 3 a close second and third) one of the best things about Britain. When, a few years ago, the government cut its funding to the World Service, it showed a callous disregard for the three million plus people to whom it is a lifeline, and a culpable ignorance of the benefits it brings to this country: which is why, of course, when they belatedly woke up to its value as the most useful ambassador of all, the funding was restored.

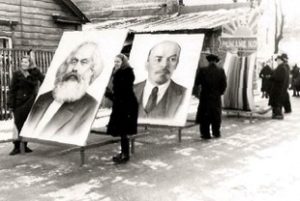

Street Parade, Soviet Estonia in the early ‘60s.

Much as I love such items as the one about the dung beetles, it is memories of what the World Service meant to people I met in Soviet Estonia in the ‘60s and ‘70s that make me so passionate about it. The two elderly men, old friends of my parents who had risked listening to it throughout the years of Soviet rule, knew – as many of my younger relatives did not – that all was not as it was said to be. No, I had to tell my cousin, Eva, a convinced Communist, we did not send little boys up chimneys any more and Yes, we could leave the country any time we wanted. She found both these things hard to believe.

And then there was the young man on the train to Viljandi (my grandmother’s birth place) who heard us speaking English and told me how much he would love to have a copy of Fowler’s English Usage. Another clandestine listener to the BBC.

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?