For the thirty years I worked as an editor – a job which could be described as being a Book Doctor, but a doctor whose duties don’t end with caring just for the book but also for the person who wrote it – I would tell authors crushed by bad reviews to ignore them unless they felt the reviewer had made a valid point, in which case best to take it on board.

Well, as an author myself and recipient of a less than friendly review in a journal so prestigious that everyone told me I was lucky to be there, I realised this is more easily said than done. I would not prefer to be there. I would rather have had a few friendly words in a parish magazine than that rambling put-down in a journal with a world-wide circulation.

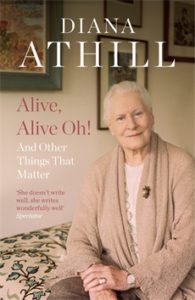

Image: © OK David

In a vain effort to follow my own advice, I tried to ignore the review after deciding (as so many authors in the same situation have done before me) that there was nothing to be learnt from it, but the next step was even less easy to take.

Even if – in my estimation – the reviewer had it all wrong, it still rankled. Who was this person who had taken such a dislike to me and my poor book? Why hadn’t they handed it back to the Literary Editor and said it wasn’t worth reviewing (as my friend Diana Athill does, if sent a book in which she can find nothing to like)?

Pondering this question led me, inevitably, to the www (not available to my authors, as I retired more than twenty years ago) where I discovered that the person who could find nothing of merit in my book had been on the permanent staff of the offending journal. I began to fantasise about their state of mind. I even began to sympathise, having had very rough treatment from my own employer. Ah yes, I thought: here is someone being given the occasional unimportant book to review to make up for past wrongs . . .

The next step, was to moan to friends – writer friends – every one of whom came up with similar stories and one of whom said she knew the reviewer, who was a very nice person but literal-minded and with not much sense of humour. Both these qualities (or lack of them) figured. By no means all my friends had liked my book, which made me like them no less: we need the literal-minded, and a sense of humour often indicates a cruel streak. Nevertheless, it was bad luck for mine to have been given to that particular reviewer and I wish that he had taken Diana’s line and turned the job down.

But, of course, to quote the Pub Landlord ‘It is Much More Complicated than That’: reviewers get paid and not everyone can afford to turn work away. Even so, the system provides fertile ground for an abuse of power where the writer is at the mercy of someone who may simply have got out of bed on the wrong side, or happened (in the case of a memoir) to have liked someone the writer doesn’t like.

There is, of course, a way round this for the writer. No one can make anyone read a review and there are those who, like my own husband, avoid them altogether. He has never read the two-page diatribe in a long-ago London Review of Books in which he was accused of not knowing how to write English. My ‘bad review’ wasn’t anything like as fierce as that, nor as far off the mark.

Of course, it goes without saying that reviewers must be free to write whatever they like, but that doesn’t mean the rest of us can’t wonder why so much space is given to reviews which deter readers rather than sending them out to the nearest bookshop.

Many thanks to OK David for use of his image, originally drawn for the Hatchet Job of the Year Award. See more of his work at www.okdavid.com.