Not long ago we made an unfortunate choice of house to rent when spending a few days in a part of Derbyshire we hadn’t been to before. Not only was the prettily named village – which had been photographed from vantage points we were never to discover – not a village, but the house looked unwelcoming from the start.

Described as a cottage, but with all signs of its cosy cottagey past eradicated, the room the front door opened into was as bleak as the parlour of a funeral home. A giant tankard of artificial flowers, which left no room to put anything else there, stood on a low table in front of a sofa which looked as though it had never been sat on. The table was made of wood or some kind of wood laminate and at least didn’t, like the glass dining table, clang every time you put something down on it.

The dining table we had to use, for there was no alternative, but a choice could be made between having a bath and not having a bath. After needing to be hauled out of the rimless, oval shell that stood, on claw feet, in the middle of the room, out of reach of the the tantalising array of expensive soaps and unguents, I decided – in spite of the fun to be had with the Waterfall Tap – that once was enough.

Only the bedroom was hazard-free. The owner of the house had not yet indulged in the ‘careful deployment of the aesthetic of subtraction’ which one bed manufacturer promotes but, as we could see from the neat pile of interior design magazines (the only reading in the house), our landlady was a compulsive follower of fashion, and it could be only a matter of time till she turned her attention to the many possibilities to be had with a bed.

As for the kitchen, this was a minefield of unfamiliar gadgets and it took a phone call to find out where the cutlery drawer was: hidden in the recess of what looked like just another shelf.

I have been reminded of this sterile environment by hearing a young man on the radio talking about how empty his first rented room seemed, after leaving a home which had been full of things.

It takes time to accumulate the clutter which spells home but even a young person used to have a few books and copies of Time Out or NME. He or she might even have had a picture of their mother and father, or favourite dog.

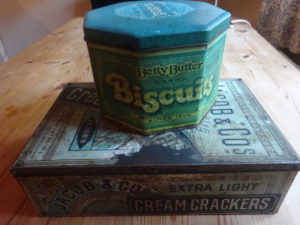

All these now, and the communal television set which brought flat-sharers together, are contained in a small metal box, no bigger than the palm of your hand. Gone are the days when the only metal box was the biscuit tin and every unnecessary object, jostling for space, had a history. When books lined the walls and littered the floor. When all around was the stuff of memories, of lives lived and living.

No wonder the young man felt desolate and yearned for the comfort of things.

*This is also the title of anthropologist Daniel Miller’s book which catalogues the possessions of the inhabitants of a single London street: an exercise carried out before the electronic takeover and the advent of commercial de-clutterers.