Housebound for a few days by a lingering malaise and fearful, as I come within days of my 85th birthday, of wasting any time, I took the plunge and began the process of de-cluttering the house in which I have lived for more than fifty years. Clothes would be easy: they barely fill a cupboard but, even so, contain heirlooms. The beautiful wine-coloured dress that a generous friend (now permanently housebound) gave to me forty years ago. The hideous baby-blue jerkin bought, one lunch hour, from a stall in Oxford Street. Both too venerable and memory-laden to put in the Oxfam box. They will continue to fill space until I am no longer around to save them.

Other sacrosanct space-fillers are the Je Reviens bottle that I had on my bedside table in the labour ward and the faded photograph of my husband and me that stands in a frame beside it: taken soon after we had met, as I can tell from my outfit, bought to make myself look eligible when I was on the register of the Heather Jenner Marriage Agency . . . .

So far, so good. The bedroom presents no serious problems. The hundreds of books that fill the stairwell and every other room aren’t a problem either. It is all the paper stuff – the letters and diaries and children’s drawings and obsolete account books (2 x white wine £7) and fearsome-looking legal documents and drafts of unfinished novels . . . . It is these and the photographs – especially the photographs – that are so hard to dispose of.

As I braced myself and, for the first time, threw away a person, I felt like a murderer. But the disquiet at breaking this taboo didn’t last long and I was soon throwing away photographs of my parents, my son and his son, schoolfriends, et al, as though there was no tomorrow. Which there isn’t. Or not much of one.

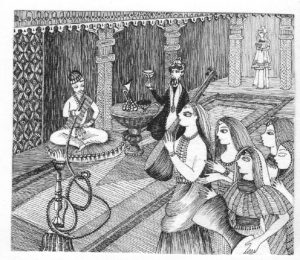

Hard as the initial step was – reminiscent of jumping into that cold Finnish lake, when honour-bound to join in a communal sauna – getting rid of photographs is quick work. Infinitely slower is all the other stuff and, as I battle my way through a lifetime’s accumulation, I wonder at the stamina of serial biographers. Of course, they are mostly trawling through papers which a professional archivist has already put into some kind of order. They are not going to find, as I have, the originals of illustrations for a children’s edition of The Arabian Nights interleaved with handwritten notes to my deaf father-in-law: ‘I never have oatmeal or orange juice or prunes for breakfast’, nor

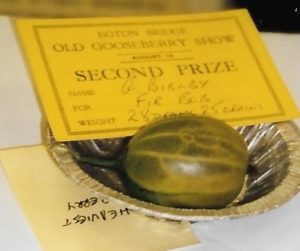

Hard as the initial step was – reminiscent of jumping into that cold Finnish lake, when honour-bound to join in a communal sauna – getting rid of photographs is quick work. Infinitely slower is all the other stuff and, as I battle my way through a lifetime’s accumulation, I wonder at the stamina of serial biographers. Of course, they are mostly trawling through papers which a professional archivist has already put into some kind of order. They are not going to find, as I have, the originals of illustrations for a children’s edition of The Arabian Nights interleaved with handwritten notes to my deaf father-in-law: ‘I never have oatmeal or orange juice or prunes for breakfast’, nor  the picture of a prize-winning gooseberry stuck to the cover of an ancient issue of Isis which has in it an article by John Gross who, in those days (February 1957) seemed to me like just another nice Jewish boy . . . .

the picture of a prize-winning gooseberry stuck to the cover of an ancient issue of Isis which has in it an article by John Gross who, in those days (February 1957) seemed to me like just another nice Jewish boy . . . .

And what about everything – letters, postcards, scraps of paper – written in languages I don’t know?

It was lucky that my aunt, adrift in Rome during the last months of the war, had been spending time with an American soldier and was practising her English for, in a letter dated 16.1.45 – addressed to my mother, to whom she always wrote in Russian – I learnt not only of his existence, but also that he had promised to marry her. But when I visited her in Trieste, a few years later, there was no trace of him.

And so it goes on. On June 6, 1948, the headmistress of my boarding school wrote: ‘Dear Parent . . . We are considering having a medium-weight brown coat and skirt, to be worn with a tussore blouse, instead of the brown winter frocks . . .’ Quite a bold suggestion when clothes rationing was still in force.

The next item to surface is an alluring recipe for Peach Clafoutis, which will now join all the other untried recipes in the THROW pile. But into the KEEP box will go my baby son’s cheerful picture of a royal threesome, alongside a festive card from Camden Register Office which has reminded me that today is my Wedding Anniversary.