One of the many things I didn’t know about dying and death is that you can’t scatter ashes just anywhere and it was enough for me to hear from the funeral director that I would need permission to carry out my plan to go to a spot in Regents Park which R particularly loved, for me to drop this idea, and to ask no more questions. I don’t therefore know if what we did the other day was illegal. All I know is that it didn’t feel illegal and couldn’t possibly have done anyone any harm.

My son was in England. So was my daughter-in-law, who has a wonderful voice and would have sung a traditional lament as we said our final goodbyes, but we feared attracting attention as we scattered the ashes in the churchyard of one of the little parish churches that R had so loved and that he and I had visited together.

Far from London, where he had lived most of his life, and further still from his birthplace but, as I comforted myself and told my young grandson, not far at all from his ancestral home, just across the Scottish border . . .

It was on a very wet Sunday morning that we had arrived in Selkirk, some twenty years before. The town square was empty except for a statue of Mungo Park.

Desperate for a cup of coffee, we tried a few side streets. Not a sign of life. Back in the main square, we noticed an open side door in the one grand building.

Inside we found an office and a helpful lady who explained this was the Court House and told us that Walter Scott had been the Sheriff here for almost thirty years. Surrounded by files and with a computer, which seemed strangely out of place in this mausoleum, it didn’t take her long to establish that the Harbisons had once lived in this town and she told us we would find their gravestones in the churchyard.

On some other day, we might have found them but by now the rain was bucketing down. The sodden grass was knee-high, the inscriptions on the ancient tombstones hard to decipher, and a light had gone on in a window in the town square. We turned back and headed for it. And there, in a tea room as spartan as the British Restaurant that my mother used to take me to during the war, we had a comforting hot drink of something like coffee.

No wonder the Harbisons had fled all those years ago from this rugged little town whose townspeople were permanently at war with their English neighbours.

The ferocious Battle of Flodden would still have been a relatively recent memory: a memory vividly recalled in the little museum we came across, in a cobbled side street, when we had warmed up and dried off.

Housed in a plain but beautiful old building, the very best example of civic pride, here we learnt the war-torn history of this place, now a quiet backwater, but once the scene of endless strife.

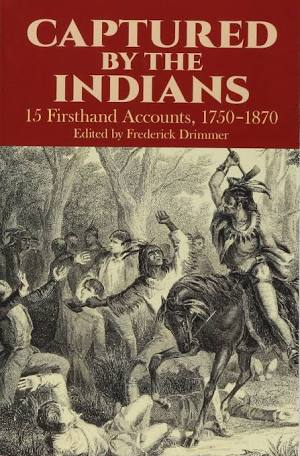

I wish I could remember exactly when R’s family had left. I think it was mid-eighteenth century; anyway, long enough ago for one of his ancestors to get herself captured by ‘Red Indians’, an experience she survived and wrote about in an account which, like other captivity narratives, still exists.

So, I am able to tell my grandson, who is proud of his own Native American blood, that his much-loved grandfather was not the first Harbison to be a writer and his memory, like that of his intrepid Scottish predecessor, will live on.