It is, of course, inevitable, in one’s eighties, that one knows more dead people than alive people, and yet it was quite a shock to realise this when my friend, the novelist and blogger extraordinaire, Jon Elkon – a good twenty years younger than me – pointed this out. Nothing, of course, would surprise Jon, one of whose fictional characters was a talking dog, but it did surprise me. How could I not have noticed?

My world is now full of people who are no longer there . . .

Strangers live in Ilsa’s flat. There is a grave – his grave – in the wild flower meadow that had been my cousin Anthony’s pride and joy. Juliet lies among her ancestors in a Norfolk churchyard.

Michele will never walk her dog on the Heath again. But I will always cherish her very last column: she had told me, only days before her death, the story of this near-miss with some randy schoolboys and I had countered with my story of a Greek stationmaster: both of us well-brought up and hopelessly naïve Jewish girls, we almost lost our virginity by default.

Michele Hanson

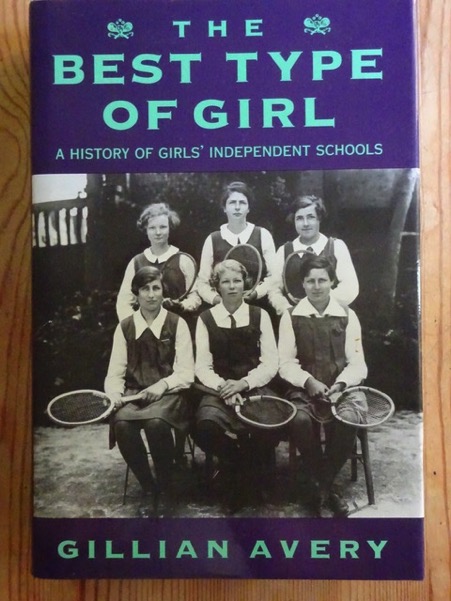

Who else? There was Gillie: an Oxford friend alongside whom I spent an Easter vacation working in a Lyons Tea Shop which would have been in the shadow of Centre Point, but there was no Centre Point. Then, some twenty years later – for Gillie died far too young – the merciless run of deaths among my authors, all in early middle age. Carol Bruggen, one of my favourites, both as a writer and as a friend: a paranoid schizophrenic, who would put on a different set of gaudy clothes each morning, to keep her spirits up. Faith Addis, who had to be dissuaded from going to writing classes, even as her fan mail mounted up and her books were adapted (horribly badly adapted) for television. Madeleine St John, whose gem-like Women in Black far out-shone her later, prize-winning novels and, later still, Gillian Avery who got tired of being looked down on by her academic husband and his high-table friends for writing children’s books and came up with a splendid tome, replete with notes and bibliography.

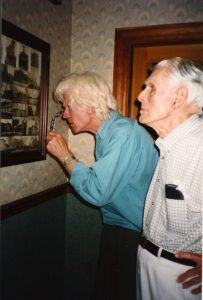

As the list of the dead gets longer and longer, it is the thought of out-living those who mean the most to me – not death itself – that fills me with dread. Not so my father-in-law, who watched his contemporaries pass on with grim satisfaction. He had not wished them ill but he was glad – proud, even – that it was them and not him. The final duel between him and his equally long-living brother-in-law, who Dale had long suspected of cheating at golf, had itself the excitement of a sporting event.

My father-in-law, Dale Harbison (foreground)

Not long ago, Diana Athill, now one hundred years old, let it be known that she and one of her friends in the lovely, serene Home where they both live, count not sheep but ex-lovers to help them get to sleep.

Thanks to Jon, I may now go one step further: I may lull myself to sleep listing the dead.