Talking with a friend of my own age the other day, as we sat on kitchen chairs at either end of her small front garden, I heard, or thought I heard – still not acclimatised to the hearing-aid I should have learnt how to use before lockdown – that her late mother had once bought, and paid real money for, a ticket to the moon . . .

What else does one need to know about someone than that!

We were talking about mothers. About being them and having them. What we know about our own, and what our children and grandchildren know about us. Not an entirely comfortable subject when you reflect on those long-ago days when your child needed you, wanted only you and, for too short a time, thought everything you said and did a miracle of rightness.

How short a time those glory days lasted! I still remember my son, at a very young age, saying that I would claim an elephant was Jewish, if it was particularly clever. A wholly justified rebuke. My Jewishness, until recently, extending no further than often wondering whether someone was or wasn’t.

Not many years later, his self-assertion took more active form: overnight, this enthusiastic meat-eater turned vegetarian. A step guaranteed to disrupt family meals, the bedrock of family life. And a prelude to his untimely departure.

Of course, every child is different. Some are less impatient, more hesitant about breaking the ties with home, but each one of us needs to do it eventually, or become that sad creature, the child who never leaves.*

Myself, I took the easy way, as I discover now, rooting through old letters. I waited till there was distance between myself and my parents, and am ashamed at finding how seldom, now that I was enjoying myself at Oxford, I bothered to write home. My father’s frequent letters to me ended, almost always, with a plea that I write more often, for my mother’s sake. Her more laboured efforts (she never became fluent in written English) are more subdued. She found it harder to bear my neglect.

My son’s way of breaking free was more dramatic, but that only made his return the more wondrous, and I only wish that now, thirty years on, I could cook him his favourite roast-lamb homecoming meal. But an ocean divides us.

It was a funeral which woke me up to how much parents come to need their children. Infancy and old age have all too much in common. I could not see my husband being able to put on the carefully choreographed event from which we had just returned. Who, I asked him, is going to organise my funeral? His answer was anecdotal. It seems that when Bach’s wife died, his oldest daughter came to him and asked what they should do about her mother’s funeral. ‘Ask Mama,’ was his answer.

Of course, primitive peoples – poor people – have always known that the hordes of children whose births they could not, anyway, have avoided are not only going to till the fields but also look after them in their old age. We, on the other hand, with our 1.7 birth rate, have a bleak future. Which is why I liked the idea of spending my final years becoming acclimatised to dying, among people of my own age, and with help at hand But no one is going to sign up for even the plushest of care homes for a very long time to come and, with this escape route cut off, I envy my friend, with two grown-up daughters to look after her, whose adventurous mother had hoped to fly to the moon.

My own mother’s ambition could not have been more different. She longed not for an unknown future, but for the familiar past: to speak her own language, to see the friends of her youth . . .

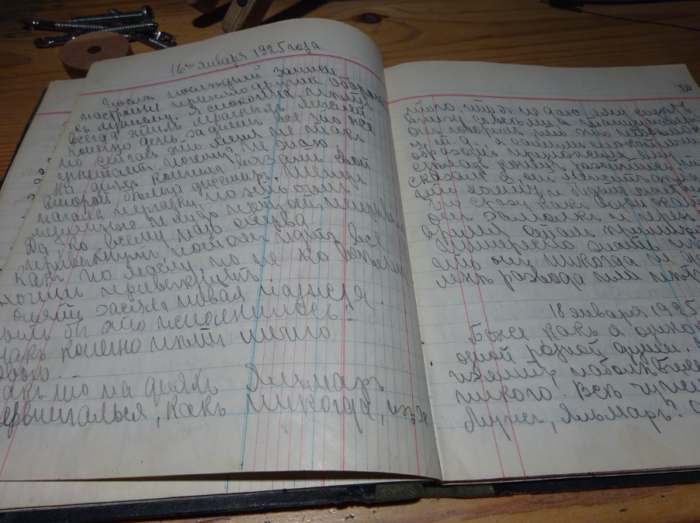

Whether I will ever see my son again remains in the lap of the gods. But, whatever happens, whoever comes into this house when both I and my husband have left it, there, among the debris, they will find my seventeen-year-old mother’s diary, trapped for ever in fading Russian script.

Unable and unwilling to read it, I will never know what she was like then, any more than my son will know what I was like before I became his mother. And that is how it should be, or so it seems to me. Parents aren’t, like friends, for knowing.

*With apologies to the many young people who cannot now afford to leave home.