I may have discovered (or, rather, been the first to recognize) a few writers, but my grandfather discovered a gold mine. Well, not actually gold but oil shale which for many years has been one of Estonia’s largest industries and, though now a denigrated substance, is still exported by them and used throughout the world.

It happened something like this: born in a small town in Belarus but orphaned at an early age, my grandfather was raised by an uncle and aunt in nearby Tallinn, and soon speaking some Estonian as well as Russian and Yiddish. English was to be added when, to escape the mandatory twenty years of military service (Estonia was then part of the Russian empire) he made his escape intending, we believe, to go to New York but – could he possibly have thought he was already there? – never getting further than England. There he found work as a tailor and, before very long, had not only married and started a family, but had his own shop.

But, though as English as could be in appearance, with his trilby and plus fours, he still drank his tea with jam, Russian-style, and dreamt of home. And as soon as his girl children were old enough to be left in charge of the shop he went back to Estonia, not just on short fur-buying trips – for the shop now sold furs as well as ladies’ outfits – but on a mission to help it achieve independence. He had already arranged for Estonian flax to be shipped to Scotland. He was now on the look-out for something bigger . . .

Some hundred or so years earlier, according to legend, the villagers of a small parish in Estonia had found that the soil with which they were building a protective wall around a camp fire was combustible. They called the substance Burning Stone.

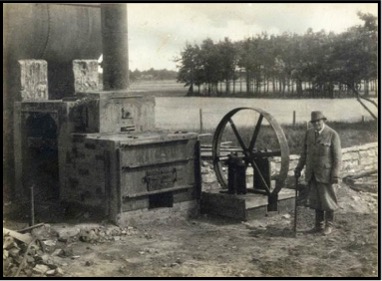

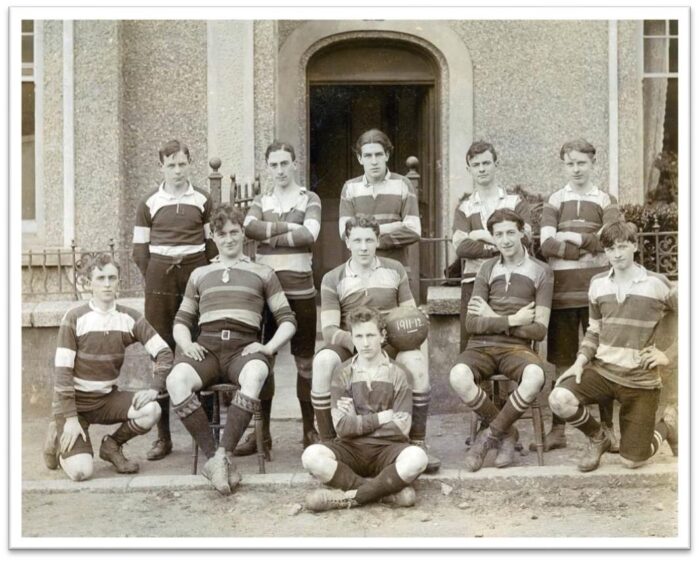

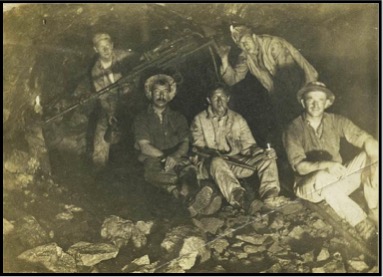

Perhaps it was this which set my tailor grandfather off on prospecting trips with his friend, Gerhard Lukk, a mechanical engineer who would have provided the know-how which my visionary grandfather did not have. Be that as it may, before long they had found the site which was to become the giant mining complex where my mining engineer father was to spend the next twenty years.

I have seen Vanamoissa only in photographs: when, in the early 1960s, I first went back to Estonia, where I had lived for most of my first five years, foreigners were not allowed to go to the mining area or, indeed, anywhere else. It took endless meetings with officials to get permission to visit the family graves. We shouldn’t have bothered. The graveyard had been razed*. There was nothing left to see.

But photographs tell me as much as I need to know about Vanamoissa and this happiest time of my father’s life, when he was doing the work he was cut out to do and had no idea what lay ahead.

What lay ahead for everyone, was World War 2. What lay ahead for my grandfather, back in England for good now, was a peaceful old age. It was very different for Gerhard Lukk. He had been (I quote) taken away from his home by the NKVD in an official black car as his five children looked on.

This, and the date of his abduction – June 18, 1941 – I was to learn only relatively recently when an Estonian film-maker, Tiina Soomet, living in Canada, got in touch with me after reading an article which I had helped to translate** on the Estonian Jewish Archive website. These were the words that had drawn her attention:

in 1919, two mining engineers, Alexander Menell and Gerhard Lukk (about whom, alas, we know very little) approach the Estonian government for permission to carry out a surface examination.

Thanks to Tiina, I learnt that Gerhard Lukk’s five children all survived the war and ultimately settled in the UK, Canada and the United States. One of Gerhard Lukk’s granddaughters had become a particular friend of hers and enlisted her help in piecing together what had become of her grandfather. In this they received invaluable help from the Netherlands Baltic Association, for it turned out that my grandfather’s friend had been not only an engineer but also Consul General of the Netherlands.

Further information began to emerge and we find that in 1942 Gerhard Lukk was sentencedby the Special Board of the NKVD to 10 years in a Labour Camp. No more is known about the last years of his life but, In June 2001, it appears he was rehabilitated (posthumously) by ‘the resolution of the Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation.’ Small comfort.

But, happily, the story does not end there. In 2022, at an official state ceremony on June 14 (the National Day of Mourning***) a plaque with his name on it was unveiled on Tallinn’s Memorial Wall to the Victims of Communism, and his granddaughter was there to see this happen.

How little has changed. The town in Ukraine where my grandfather was born is a battleground. The country where he grew up and which he so loved is in imminent danger of being invaded, once again, by its powerful neighbour.

I am glad my grandfather doesn’t know this, nor that his granddaughter can’t sew on a button. The one time I did this it was sewn on so tight it wouldn’t button or unbutton.

*The Germans overran the country in the first year of the war. Only eight Jews of the original 4,000 survived the occupation. The other Baltic countries, which had large Jewish populations, became killing fields.

**Burning Stone by Mark Rybak in the Estonian Jewish Archive

*** This day commemorates the victims of the June 13/14, 1941 mass deportations of Estonians to uninhabitable parts of Russia.