Unable to blog for the past two months and not wanting to miss November too, I am borrowing something written by a friend which I would love to have written myself.

Its author is not a writer but an artist. I only wish I could paint as well as she writes, but I have no talent whatever in that direction and still cringe at the memory of my School Certificate ‘Still Life’, even though it got me a Pass. The examiner must have been half asleep.

My recollections of Vicars Bell

by Sandra Oakins

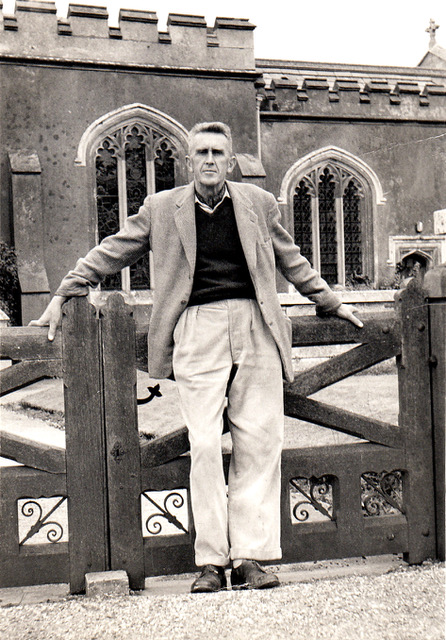

Such an odd christian name we all thought as children: Vicars, in fact it still is. His

nickname was Ticky Bell. He was tall, looked like a hawk with a beak of a nose, a

large pale mole on one side of it and grey hair that stood up like a shoe brush. He wore what I now know as a Harris Tweed jacket, hand-knitted jumpers in unremarkable natural colours and a kind of silk cravat — yellow or red. And sensible walking shoes. His wife Dorothy played the piano for our country dancing lessons, until she got tired of the repetitions (The Dargason usually got to her) when he would take over by singing the piano part. She had eyes like blackcurrants and took no prisoners. She had a large handbag that was set down by the piano, wore dresses or more precisely frocks which went below her knees, cardigans and a string of amber beads. Her straight white hair was cut short, and her fringe severe, so unlike the hair of all our mothers whose perms and curls were the thing, and every one of them kept a shoebox of hair rollers in a cupboard. The school was open house, other grown ups would come and go, we knew them too. Geoffrey Tandy, Dorothea Patterson were two. The ‘Gaddesden Society’. By name and by nature.

Mr Bell could not abide Enid Blyton, comics and make up. And television—and—the hymn ‘When I survey the Wondrous Cross’ with a vengeance. Sentimentality was not on his agenda. He gave me my very first lesson in sexism. It was at church. Quite a few of us sang in the choir and before one morning service I went into the vestry to get some hymn books, he was there in his cassock and surplice and so were the choirboys. He came up to me and told me that women (and girls) had no place in the vestry. I dare say they were allowed in there to clean but at that time I would be about 12, so that didn’t cross my mind. I couldn’t really see why I shouldn’t go in and he didn’t say why.

The other side to this was that he expected us, both girls and boys, at the age of seven onwards, to have the intellectual capacity to be able to ‘get’ Shakespeare and poetry (and I mean poetry and not verse). Dickens, T H White, H G Wells, G K Chesterton were his writers and Walter de la Mare, Edward Thomas, John Masefield, Rudyard Kipling, Ralph Hodgson, James Stephens, Hilaire Belloc, D H Lawrence, W H Davies his poets of choice. He expected us to be able to look at things we had produced with an eye to making changes. We had poetry read to us every Friday morning for about an hour. Every so often we were allowed to write our own poetry. When we thought it was finished we had to go up to his desk and show it to him. He taught us to recognise derivative ideas and how to choose the words for what we meant. We also had to write descriptions and make up stories in our ‘Rough Writing ‘ book. Once I took my description of ‘The view from my bedroom window’ to show him and he took out his Osmiroid fountain pen and carefully drew a a circle, in brown ink, round the word ‘nice’ (another of his pet hates) each time it appeared in the piece I had written. There were quite a few circles by the time he got to the end. He said “I was thinking the other

day how well you used words but nice…nice, nice means ‘neat’, is that what you

meant to say?” I think I did get to buy my own Osmiroid pen, from Mr Ward’s Post

Office, they were about six shillings. And I think we used them in school.

Mr Bell was the only bell in the school, time was called by him, and literally so at the end of playtime. Lessons were elastic and so was the learning space. Outside was as good as inside, especially if the weather was good. There was a kind of timetable, but I never saw it written down, lessons just came and went. In them we were often given the benefits of his thoughts and experiences. The days started with a bit of bible or common prayer and included reading, writing, painting, weaving, potting (in an asbestos shed), dancing, singing, gardening, walking in the woods, writing with italic dip-in-the-ink pens, spelling (that word ‘necessary’) and, in the school hall, music and movement. This was thanks to the BBC and it was about the only thing we had to do ON TIME. A radiogram in a blond coloured wooden case on legs and castors was wheeled out and plugged in, we sat cross-legged on the wooden floor then performed. Possibly the radio was supplied by the Council. They also sent, on a regular basis, large wooden crates with black painted hinges and fastenings, full of library books, that we could borrow and take home.

His teaching methods went back to basics, fundamentals. We had abacuses in Miss Taylor’s infant class. Long division and fractions were taught from first principles and then there was mental arithmetic, even my father remembered having to do mental arithmetic. We worked in groups to write and produce a ‘play’, and there were these so-called games. For one he would stand at the blackboard with a piece of chalk in his hand and he would pick an object, say a bus, and we would have to tell to him how to draw it on the board. He did precisely what we told him, with hilarious results. This was really a lesson about using words and it fooled us into being precise. He knew of course that the idea of getting the better of your headmaster was always a game with great potential as far as we were concerned.

School dinners, like music and movement and jumping over the ‘horse’, a nightmare apparition of padded brown leather and splayed wooden legs, with Mr Bell standing by to catch us, were taken in the School Hall. This pale green painted prefab building with French windows along one of the long sides, was, in wet weather, a short sprint over the playground. It had a small lobby with coat hooks and there were murals on the end walls of the actual hall, painted by Geoffrey Drewitt, a previous pupil, village scenes I think. Separate tables seating about 6 or 8 were laid out. The teachers not only served us, they sat at ‘our’ tables. We walked through the kitchen in an orderly queue and held out our plates, Oliver Twist fashion and they spooned out dinners from aluminium trays, cooked by Mrs Rogers and Mrs Bunting.

Vicars and Dorothy lived in one of the middle Ashridge Cottages, at the far end of the village next to the council houses and he cycled to work on a dark green bicycle. The house was a small and basic, to the right of the front door was his ‘study’, to the left the sitting room and at the back a scullery/kitchen. Dorothy had a wooden hut in the garden where she slept because of her having had TB. Vicars went on walking holidays, alone.

I have found that there is a black and white photograph of him writing at a desk, in the National Portrait Gallery archive. It was taken in 1948 and put there in 1996 (I wonder who by). He also has a Wikipedia entry, I wonder what he would have made of that. As John Rogers once said “He taught us common sense.” I think he would have been pleased to have us think of our education that way.