For several days, since North Korea’s nuclear capability has been back in the News and the Commander-in-Chief has been making pronouncements that herald the end of the world, I have been distracted by wondering whether that boy genius, with his pudgy hand hovering over the button, is setting his sights on Washington or New York.

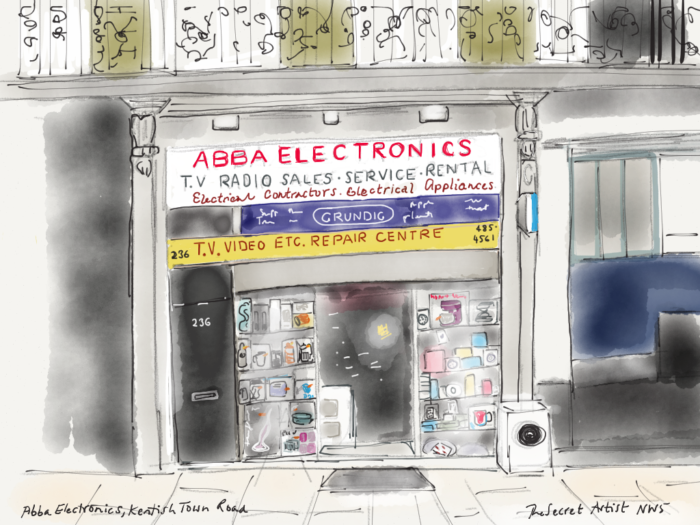

The thing is, my only son, my only grandson and my daughter-in-law live in New York, not in Washington, and the question for me is which will excite Kim Jong-un more, the destruction of the Pentagon and seat of government or Trump Tower and the lights of New York.

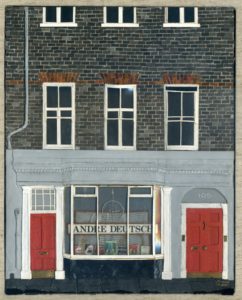

Our part of New York

My guess is the latter. Especially if he is a film-lover like his dad.

So, it was like the sun coming out when my American husband – not that you needed to be American to know this – pointed out that it won’t be Washington or New York, it will be California.

So, as my friend Pat commented drily: That’s all right, then.

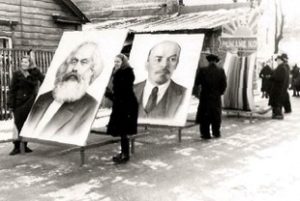

Well, no. And yet how hard it is not to put one’s own concerns before other people’s. Not long ago when, in a brief cold spell, our central heating gave out, it didn’t help to think of the plight of the refugees. The only ‘hardships’ it is easy to bear are those that are self-imposed. I wouldn’t choose to eat out of buckets (see below), but it was fun being in this remote part of India for a few days just as, many, many years ago, was being stranded in Agios Nicolaos – now a mecca for tourists, but then virtually unknown – when the only boat scheduled to stop there didn’t and sailed past in the distance.

It is also easy enough to put up with things that one knows will come to an end, like night cramps and toothache, but the end of the world . . . ? Laughter seems the only sane response and, as for other people, there will be no other people. Whether we like it or not, we are all in it together.

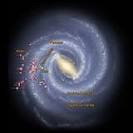

The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?