The other day, leafing through an oldish copy of the TLS, I came across a long piece about the Themersons: Stefan and Francezska who, among much else, founded the Gabberbocchus Press whose books have now become collectors’ items.

Francezska Themerson at work in her studio, 1969.

Their extraordinary careers in which she, an artist, worked alongside her poet, novelist, philosopher husband are charted in the piece which also refers to the exhibition of their work which had been held, not long before, at the Camden Arts Centre in Arkwright Road: opposite the JW3 community centre, where, as Polish-born Jews, they would also belong.

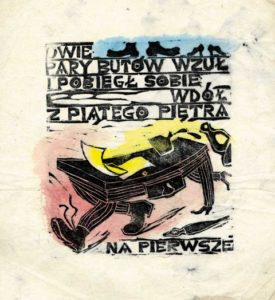

An example of Francezska Themerson’s work.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, when – in my role as jacket-supremo, a job thrown at me on my first day at the publisher André Deutsch, where I had been taken on as an editor – I was lucky enough (through the good offices of Michael Horowitz) to get Francezska Themerson to design a jacket for us, André rejected it.

‘I AM NOT GOING TO PAY FOR GREY’ is what André said.

This exceptional artist had used three colours, of which one was grey, for our modest 3-colour job and had, moreover, generously provided the colour separations which were needed in those days.

It took a great deal of angry persuasion to make André change his mind. And he never did change his mind when it came to the jacket for my husband’s first book, Eccentric Spaces, which has been constantly in print since it was first published by Knopf in 1977.

Knopf had used an Atget photograph for their edition and it remains one of the loveliest of jackets, for not only is the photograph of rare beauty, but the lettering is a perfect fit. Everyone at the free-for-all meeting at which jacket decisions were made was for it, but not André. When he heard what it would cost, he told me to ring up the French Tourist Office and get a photograph for nothing.

Such was life when André was in place. How it changed when his successor, Tom Rosenthal, took over! Tom was not one to go around switching off lights or complaining about paying for heating whenever he saw an open window . . .

But it wasn’t long before austerity began to seem a virtue as our new employer’s largesse, of which he himself was the main benefactor, began to sink the firm. Before long, after thirty-two years and with only one year to go before retirement, I was out on my ear.

My wish to take the matter of the disagreement which precipitated this to the Rabbinical Court – I had a picture of the bearded elders pinned above my desk – was discouraged by the very grand and very generous firm of solicitors who fought my case, pro bono, for four long years. I am sure they were right, and yet . . .

So much for this story of extravagance on the one side and parsimony on the other. The oranges and lemons of office life.