It is now two years since R died and I had hoped to celebrate his life by printing here something I found recently among his papers: an account of a trip he made to Alaska, at the invitation of an old college friend who, at the last moment, was not able to make it himself. R however, fully equipped for the adventure, thanks to his friend’s generosity (this friend had taken a very different path in life which enabled such excursions) did make it and I have, all these years later, come across what he made of the experience. I have not, however, had the time to make it presentable (there are parts which would be of no interest or might be considered indiscreet) so, instead, I reproduce here a detachable piece of his published writings — the preface from the 1994 Ecco Press edition of Eccentric Spaces — which I treasure, even though it did not, as we had hoped it would, land him a job . . . *

It is now more than ten years since this book was written. My own position in the world has never been more eccentric than it was in the year (1973-1974) in which I wrote it. I was out of work, a condition the book cured me of, not by landing me a job (I am still looking) but by making me think it was the right way to be.

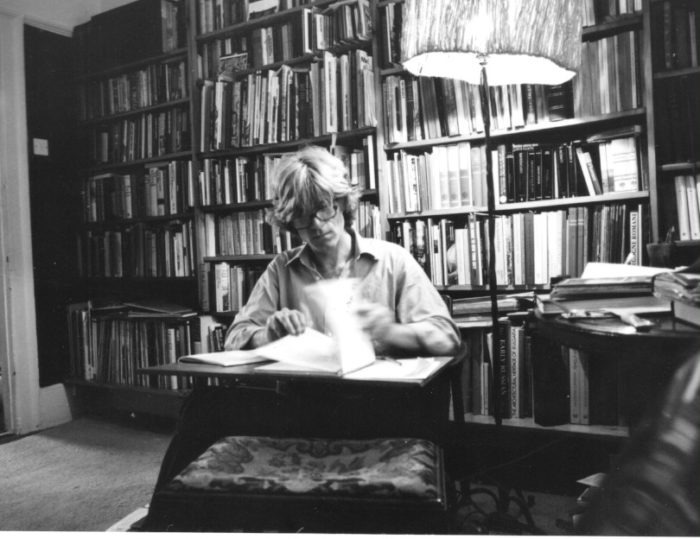

I had come back to America to find work after two idyllic years in England. At first I lived with wonderful friends, who though they had a large family and a small house still made room for me. By the time I moved into the sleazy apartment where Eccentric Spaces was written I had applied for everything I could think of, including a post at the Missouri Botanical Garden, and been turned down.

So here I was living on the fringe of the university (Washington University, St Louis) where I used to teach, not allowed to take books from its library, stuck in a student slum, and feeling like a conspirator when I visited my old friends in the English department.

Writing filled up that empty space in the most miraculous way. I am a far from mystical person, but I was propelled to begin by a dream. I mean one of those events which happen to you in the night, not an ‘idea’. Though it would be self-indulgent to recount it here, I think it would have convinced anyone. From that moment I have not really been capable of the same depths of unhappiness as before. From then onward I could say with conviction that everyone contains his own happiness within him.

Vicissitudes, after that, were provided to give something to rise above. In the third week someone came to reclaim the desk I was writing at (borrowed like everything else in the room. My own things were laid out like a simplified map along the base of one wall).

So the next morning I sat on the floor with my back against the wall and locked myself in with a white plastic coffee table. There were further deflections, including, worst of all, two months in which I couldn’t get a word out and read most of the books treated in chapters five and six. The room was bare except for a series of pictures I borrowed from the local library and stared at when I got stuck. It was in that way through Hunters in the Snow that Bruegel made his way into the book and I realised he was my favourite painter after all.

This all sounds very solitary, which it was, but I had some fathomless support from three people in St Louis and one in London, who are mentioned in the book’s dedication and acknowledgments, and who each in a different way made that year one of the happiest.

If it isn’t already, the story becomes tedious when it comes to the stage of looking for a publisher . . . and it become drearier still when one compiles things like a list of where it wasn’t reviewed. It is a book which has made its way obliquely, not in public channels of communication, but in friends (or strangers) talking to each other. I have met some of the people I value most through its agency, have re-met good friends from the past, and am very glad that this book for which I have a really lamentable fondness can now start on its travels again.

*Not many years previously when R had been granted a Guggenheim Award, he had been tactfully described by that august body as ‘an independent scholar’.