All publishers, past and present, have stories about authors they have missed out on, but not many will involve having the soon-to-be-successful writer on their premises. I was reminded of this by coming across one of Andrea Newman’s novels in a charity shop the other day . . .

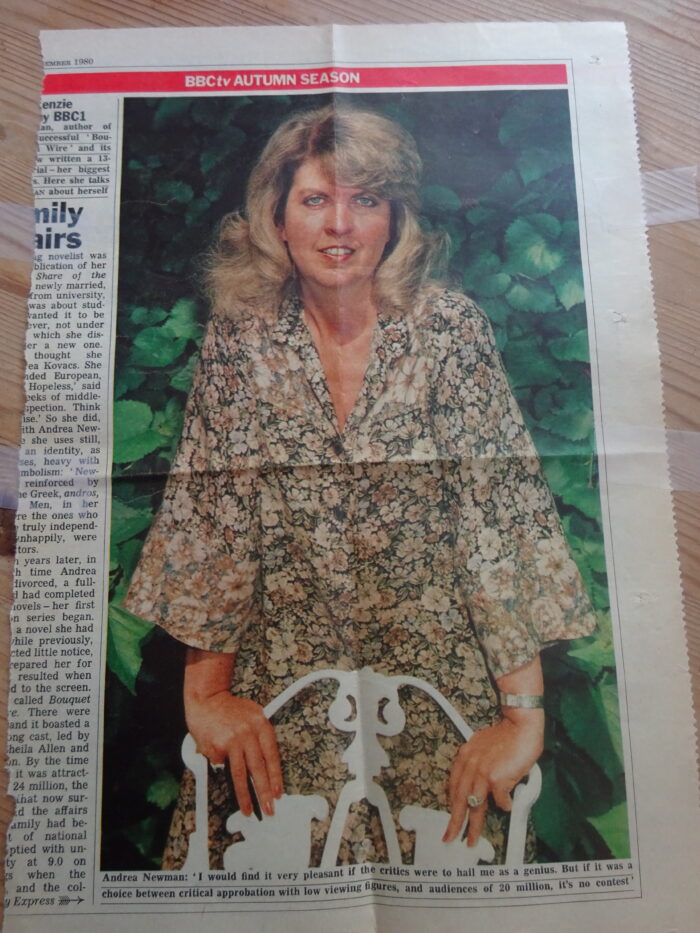

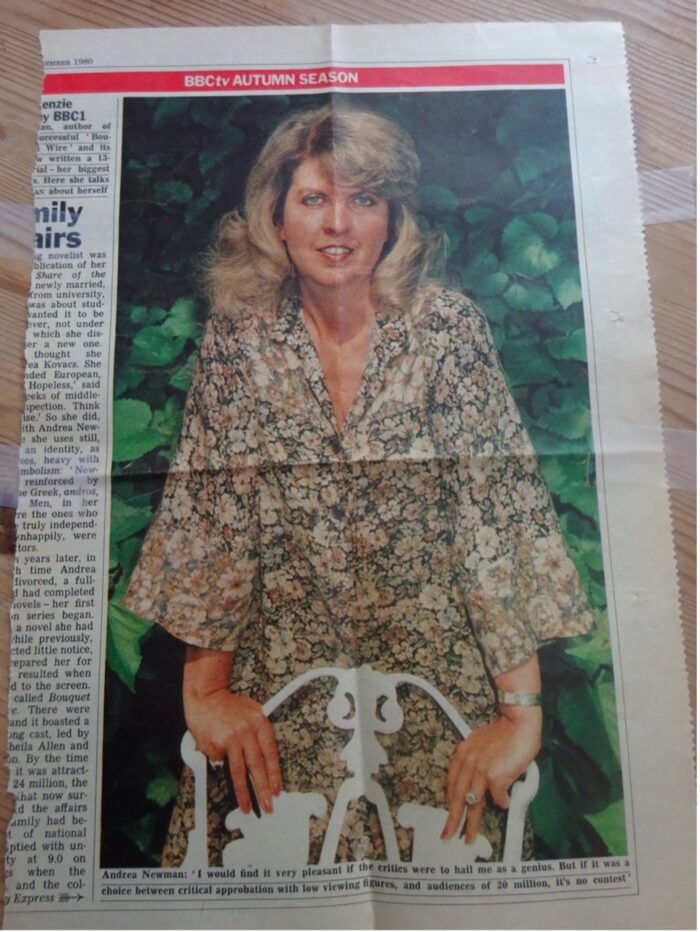

The first thing I had noticed about Andrea was her ring. Which would have pleased her. For she had bought the large diamond for herself.

The two of us were in a kind of mini-bus along with several other people who had been on the flight from London to this Majorcan resort and were now being dropped off at the various hotels.

Hers, reached before mine, was on the front, and I did not expect to see her again nor think that, with her bouffant ash-blond hair and diamond ring, we would have much to say to each other. It was a surprise, therefore, when the next day, as I looked down from the promenade, I saw her lying flat on the sand, reading what looked like a very long poem . . .

Andrea, it turned out, was a writer who, unlike most published writers, was sensibly hedging her bets by taking a further degree. She did not take it for granted that she would complete another novel or have the film rights of it bought if she did, and it was Paradise Lost she was reading on the sand.

From now on she, who had come to recover from a broken love affair and I to get a good night’s sleep while my baby son kept his father awake in my stead, spent a lot of time together and, thanks to the tour company preferring not to have people dining alone, it was arranged for me to have all my evening meals with her at her seafront hotel.

It was thanks to this that Andrea discovered that though I knew more about Milton than she yet did, there was a subject about which she knew a lot and I knew nothing, and that was alcohol. It made no difference when I told her I didn’t like the taste. Every evening she would try me on something different till, in despair, she ordered a very sweet liqueur . . .

It would have amused her to know that some years later, Henry McNulty, the suave anglicised American who was drinks editor of Vogue, complained that I had a ‘child’s palate’, though he did congratulate me for my contribution to his book. I had invented names for many of the extravagant concoctions in his Vogue Guide to Cocktails.

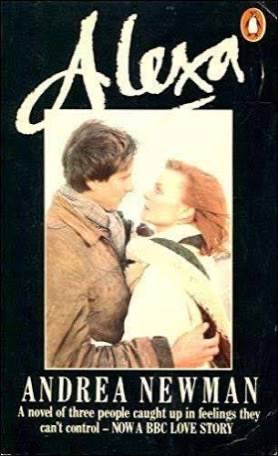

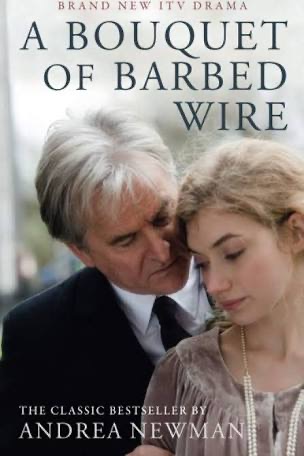

I was never to edit Andrea, though I might have done had André paid more attention when I brought her round to see his office. This was by way of research. She was planning a novel in which the main male character was a publisher. Had André turned on his charm, we could have published Bouquet of Barbed Wire which, when adapted for television, had 20 million viewers.

It is also not impossible, for Andrea liked older men (well, actually, she liked all men), that she might have brought the book to life. Although an early marriage to a local boy in the provincial town where she was born allowed her – with her strict Catholic upbringing – to have early sex, that marriage didn’t survive what London had to offer. I listened raptly to her tales of group sex, and was shown photographs, both lewd and sentimental, taken by the rich lover who had recently deserted her but who would soon be replaced.

Not only a sexual adventurer but also an astute and self-taught businesswoman, Andrea was in many ways ahead of her time.

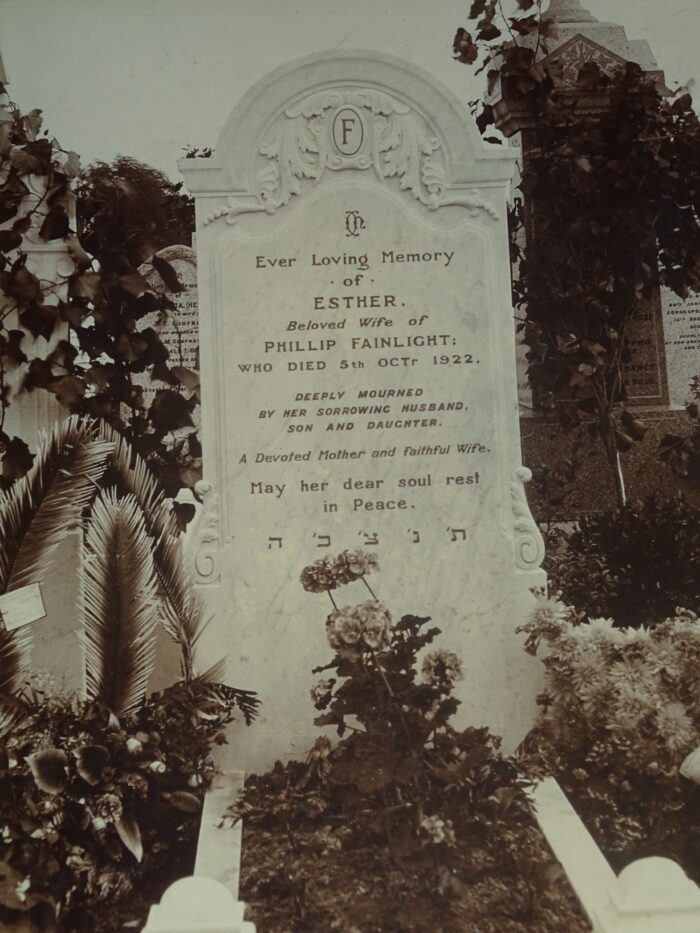

And though our friendship ended in tatters, as her friendships with women always did, I remember her with affection and some admiration. She not only wrote well but, for all her metropolitan success, did not forget the past. She remained a dutiful and loving daughter, though what her pious mother made of the novels she typed up for her daughter and then put in the fridge for safe-keeping, we can only guess.